The Indian nation faces an economic crisis. In turn, the Indian economy faces a quality crisis. The key to success in competitive international markets lies in providing excellent product and service quality. India has a poor track record on both counts.

As leading world class competitors raise their standards of quality, the level of quality expected by consumers continues to increase. In response to the demand for higher quality products and services, a number of firms worldwide are adopting new management practices. The term “Total Quality Management” is often used to describe these practices.

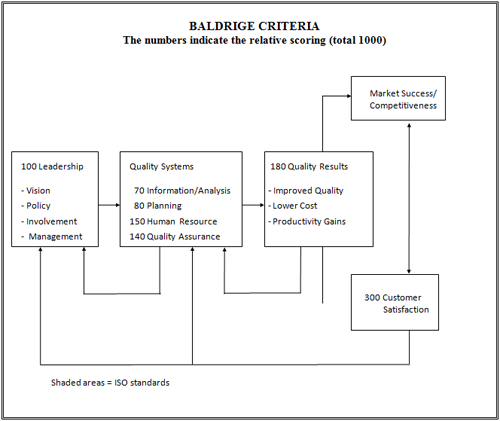

Total Quality Management (TQM) is a relatively new approach to the art of management. It seeks to improve product quality and increase customer satisfaction by restructuring traditional management practices. The application of TQM is unique to each organization that adopts such an approach. However, over the past four years, several companies in the USA have built their TQM model around the criteria used in the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award. And with rewarding results.

The award is presented annually to up to six companies - two each in three categories: manufacturing, service and small business - that pass a rigorous examination process. Increasingly, companies view the criteria outlined in the Baldrige Award application as useful diagnostic tools for evaluating the effectiveness of their management practices. Xerox uses the criteria for their international operations. Hence, Modi Xerox is already subject to the same. Likewise, Goodyear Tyres.

Companies that conduct a Baldrige self-assessment, usually find that improvements are needed in all seven categories (refer box). However, few managers have the required understanding of quality management or the Baldrige categories to make concrete proposals about “how to go from here to there?”. Yet, according to Baldrige judges and examiners there are certain litmus tests that managers can apply to identify strengths and weaknesses and suggest improvements.

Category #1: Leadership

The twin pillars of this category are symbolism and active involvement. Symbolic acts are required to cement the importance of quality in the minds of the employees and to elevate it above financial and efficiency goals, which have long dominated decision making. Bob Gavin, the former CEO of Motorola, restructured his policy committee meetings so that quality was the first item on the agenda. After quality issues had been discussed and before financial matters were introduced, he would walk out. David Kearns, the former CEO of Xerox, held up a vital new product launch because of “minor” quality problems, despite strong protests from the sales force.

To the dismay of many chief executives, heroic acts are not enough to ensure a successful quality programme. It takes day-to-day leadership as well. This can take many forms, but whatever the form, senior managers’ day-to-day quality activities must involve real commitments of time and energy and must go well beyond slogans and lip service.

One way judges separate rhetoric and reality is by reviewing log books and calendars of chief executives. Some CEOs in India are likely to pass this test: Rajesh Shah, Mukand; Chandra Mohan, Punjab Tractors; Dinkar Alva, Bombay Dyeing; K J Davasia, Mahindra and Mahindra; Dr J J Irani, Tata Steel; Ramesh Daga, Gujarat Heavy Chemicals. Each is a recipient of the Qimpro Gold Standard.

Category #2: Information and analysis

The company’s information base, covering all critical areas: customers, competitors, employees, suppliers and processes, must be comprehensive, accessible and well validated. This category is more important than its point total would suggest.

A company’s approach to benchmarking - how it collects and uses information on other organizations’ practices and performances - is also assessed in this category. The truly excellent companies use benchmarking as a catalyst and enabler of change. They seldom confine the search to direct competitors: Xerox has benchmarked American Express’ billing processes and L L Bean’s approach to distribution.

Unfortunately, most applicants for the Baldrige Award score poorly in this category. This should be no consolation to Indian companies. It is encouraging to discover that some pioneering effort is being made by companies such as Mafatlal Fine and Marico in the area of benchmarking.

Category #3: Strategic Quality Planning

Examiners look for two or three specific goals in a one to two year period, and the fact that the company can tell, explicitly and specifically, what they are going to improve and why. Endless promises and laundry lists of objectives win few points, as do hazy, ill formed goals. It is far better to seek “a 20% improvement in the reliability of our three major product lines” than it is to propose a grandiose objective like “being recognized as the world’s best metal-working company”.

The best quality plans incorporate the findings of benchmarking visits, use customer data to drive goal setting and improvement activities, dovetail neatly with the business planning process, and provide an umbrella for a constellation of quality initiatives and projects. At the winning companies, they also include aggressive “stretch” goals: staggering rates of improvement.

Mukand has stretched its improvement goals tenfold. Most other practitioners of the quality improvement process are content with threefold increases.

Category #4: Human Resource Utilization

To see if empowerment really exists, examiners look at the ability of frontline employees to act in the interest of customers without getting prior approval. Within the factory, do shop floor employees have access to a “stop the line” button that they can use to halt the assembly line if they detect quality problems?

There are other more tangible tests of empowerment and involvement. The number of employee teams is one; another is the number of employee suggestions. In both cases, effectiveness matters: the volume is less important than the per cent that are implemented. Otis India and Modi Rubber have a relatively high implementation rate. But can it compare with Japanese companies that implement three suggestions per employee per month?

Quality training involves a package of skills that includes increased awareness, problem solving tools, group process skills, and job specific skills. All are necessary and all must be deployed widely. Modi Xerox and Modi Rubber are well organized in this category.

Category #5: Quality Assurance of Products and Services

The poorest performing companies have little understanding of their fundamental processes. At a high-tech company, a key process might be new product development; at a hotel, it might be guest registration and departure. But they have little knowledge of their business and support processes, such as billing, customer service, engineering changes, and have made little effort to reduce their defects or cycle times.

Companies that have received the ISO 9000 certificates are likely to satisfy the requirements of this category. Most Indian companies experience a voyage of discovery when flowcharting their hundreds of processes.

Category #6: Quality Results

Examiners look for “meaningful trends”; they are not impressed by a single year of stellar performance, or improvements in areas of no strategic significance.

Category #7: Customer Satisfaction

This is the most heavily weighted Baldrige category, and the one that many examiners turn to first. Companies must show that they possess customer information from a wide range of sources and that their measures are objective and validated, not anecdotal. A common failing is to assess only current customers, ignoring those that have been lost or are still being pursued. Lost customers have a great deal to share about their sources of dissatisfaction; a competitors customers can help pinpoint vulnerabilities.

Winning companies set their sights at customer delight. Their goal is to exceed expectations and anticipated needs, even if customers have not yet articulated their needs. The Sony Walkman is an example of a product that meets this test.

This is the category that is the heart of TQM. Customer driven quality. Yet, this is the category that is the most difficult to implement....owing to frozen mind sets. Can Indian companies set standards based on changing customer needs? Are our processes flexible enough to accept change?

In summary, winning the Baldrige Award demands excellence in: planning to meet the customer’s quality needs; controlling factors important to the customers; improving areas critical to the customer. Managing for quality using the quality trilogy. The journey is rough. Winners of the Baldrige Award commonly worked towards this goal in excess of five years.

CREDITS: Suresh Lulla, Founder & Mentor, Qimpro Consultants Pvt. Ltd.