Shoddy products have not only damaged India’s Standing as a reliable exporter, but have also caused huge financial losses for all concerned.

To put it baldly, quality is not one of the strengths of Indian industry - not by a long shot. And by now it is equally plain that quality is the one factor that could make the difference between stagnation and growth in Indian industry in the years to come.

By and large, Indian goods and services are shoddy, and worse still, expensive. This is the main reason why India has not made any headway in the international market. Its share of world trade has fallen to a dismal 0.4 per cent from around 2 per cent in 1950. Considering the fact that we boast of a continental-size economy with adequate resources, in terms of both raw materials and an educated work force, our performance leaves much to be desired.

A dismal picture, yes, but even in this land of industrial pigmies there are giants: Bajaj Auto, Kirloskar Cummins, Tisco, Century Enka, Telco, and a few others are turning out products that easily rank with the best in the world. How and why have these companies flourished while others have floundered, in good times and bad?

The answer in every case, which indeed is a truism and may sound even naive, is that these companies have emphasised the word ‘quality’ as a watchword in their management styles.

Permanent commitment

In its narrowest sense, quality means “fitness for use”. In a broader sense, it is a sweeping overhaul in corporate culture, a radical shift in management philosophy to a permanent commitment towards continuous improvement in everything that a company does towards customer satisfaction.

The value of quality can, really be guaged in the tremendous cost of ignoring it. In those terms, it is difficult to quantify this cost, but management experts agree that if the effort were made it could well be the biggest item on the list of ‘hidden’ costs of companies. The Indian Association for Quality and Reliability estimates that, in India, the cost of bad quality, as a result of rejections, rework and other consequential expense, is about 20 per cent of the value added domestic production of the industrial sector - which is around Rs.34,000 crore in 1987-88. That works out to a loss of Rs. 6,800 crore!

This phenomenal amount of money is a complete write off for all concerned. If it were to be saved, consider the wonders it could do for the combined financial performance of the industrial sector, to say nothing of monies going to the government in the form of increased corporate taxes. And then, there are those who say that even 20 per cent is a conservative figure. Executives of some companies, which have stringent quality control measures, say that the cost of bad quality is possibly as high as 35 per cent of sales in some cases.

In the US, it is said, a typical company spends something like 20 to 25 per cent of its operating budget in finding and fixing mistakes. If Indian companies were to initiate similar efforts to make their products internationally competitive, the long-term savings could be enormous. Bad quality combined with increased competition cannot but be the undoing of a company. Already industrial sickness has reached alarming proportions and at the end of June 1987 there were as many as 160,000 sick units with outstanding credit, of Rs.5,757 crore.

Pitiable productivity

Besides poor quality, productivity of Indian industry is appallingly low; it has been estimated that Japan’s productivity in terms of value of output per man is about 12 times that of India’s. And as if that were not bad enough, large numbers of Japanese companies have active plans to increase productivity by 300 per cent in three to five years.

On one point there is no dispute: people want quality. What can be disputed is perceptions.

For many a manager, quality means quality circles at the shop floor. This is because, in his opinion, the blue-collar worker is the cause of poor quality and therefore any improvement has to begin at the shop floor. Joseph M. Juran, a pioneer of quality consciousness, thinks otherwise. He opines that quality should begin at the top and filter down. Most gurus on quality agree with this principle.

Whatever be the perceptions, if India is to compete in the world legitimately, it will have to learn to convert the Cost of bad quality into gains. According to Suresh Lulla of Qimpro Consultants, which specialises in the business of quality, “Costs can be converted into solid gains by focusing on the serious chronic quality problems, which can only be tackled by top management.”

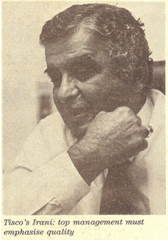

True, the Indian companies which have consciously adopted quality as a way of life and survival are those whose chief executives have taken the initiative. Take the giant steel maker Tisco. Despite the fact that it functions in the rigidly controlled steel sector, the company is the epitome of efficiency and dynamism. Why?

Says Tisco president J.J. Irani, “In our opinion, management is totally responsible for the quality of a company’s products. The message of quality and the benefits arising thereof can be significant only when all members of the workforce receive, assimilate and act upon this message. The management has to carry the workforce with it, and the leadership provided by the top management towards emphasising the importance of quality is vital.”

All-round control

Tisco does not follow a single methodology, vis-a-vis quality. A quality assurance department ensures systematic control at every point of the production process. Inter-departmental quality improvement competitions are designed to ensure that pre-set targets for various quality parameters are met. Management task forces identify facilities required for quality improvement in different departments. Based on their recommendation, appropriate capital expenditure is incurred.

On the shop floor, quality circles motivate the employees to give of their best. Says Irani, “Our efforts in quality improvement are not confined to the work place alone - the township,. the administration, the services and the hospital, all are given due importance in our drive towards total quality improvement.”

Hindustan Motors, maker of the Ambassador car, is an interesting company in more ways than one. Their earth moving equipments division in Madras is a classic example of what quality consciousness can do, both in terms of reducing costs and improving efficiency. As Ramesh Daga, executive vice-president of the division, explains, “We weren’t planning for quality before. But as a result of our exposure to Japanese companies (through collaborators) and the need to improve efficiency, two to three years ago, we actually began to plan for quality.”

This was done by emphasising quality education to every individual in the company, starting from the chief executive down to shop floor personnel. Daga is convinced that “quality improvement will, come through human resources development”. The company spent around Rs.70 lakh on developing an Education Centre for Management. This was backed up by modernising the plant and equipment. It also introduced a quality improvement programme for management and workers. The result: a whopping saving of around Rs. 50 lakh on a recurring basis on quality-related costs.

QCs: part of a total programme

The concept of quality circles is not entirely new in India. The first QCs were formed here around the early eighties. But they have not been an unqualified success. This is because QCs by themselves can’t bring about change, but are effective only as a part of a total quality improvement programme.

Their emergence is closely related to the history of quality control in Japan. Japan’s, decision to sell abroad, after the second world war, is well known. But since its products, though cheaper, were qualitatively inferior, acceptance level was low in the industrially advanced European countries and North America. The Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers (UJSE) undertook the task of improving the quality of Japanese goods.

Intensive work. This was initially done by inviting experts on quality management such as Deming and Juran. The fifties were a period of intensive training. for managers and supervisors. Then the question arose, should the same training be given to non-supervisory personnel? So, in the early sixties, companies began to offer training to lower level workers, but only on a voluntary basis (for other levels the training was mandatory).

This was the birth of QCs in Japan. These training circles have become so popular in Japan that today there are around 10,000 of them with member ship in excess of 10 million.

A QC is a small group (10 to 15 people) of employees from the same work area who meet every week. The members identify, analyse and resolve work related problems, not only to improve quality, productivity and overall performance of thy organisation, but also to enrich the work life of the employees. The creative instincts of the worker are encouraged.

Need of support. If QQs in India have not been too successful, it is mainly because of no active involvement of higher management. However, in companies like Bajaj Auto, the concept has clicked. There are 146 QCs in operation in the company with the full support of the management. Some other companies, like Hindustan Ciba Geigy and Maruti, are among those Where QCs have been successfully handled.

As Suresh Lulla of Qimpro Consultants explains, “QCs will be successful only if the company adopts the total quality management philosophy. This encompasses all operations of the company QCs by themselves cannot bring about any significant tangible results within the company.”

Small are conscious too

But it is not true that only the larger companies are quality conscious. Certain small and medium sized companies have also done exceedingly well, in both domestic and export markets; this can be attributed to their quality conscious and customer-oriented approach to business. For example, Perfect Machine Tools (PMT) , a company with a turnover of Rs.40 crore. Says D.L. Shah, chairman and managing director of the company, “I have oriented my efforts towards customer satisfaction. This is done by implementing the suggestions I get from my clients vis-a-vis my products.” An awareness of customer needs has enabled the company to improve its quality, by virtue of which the company’s exports (mainly to Japan) crossed Rs.2 crore last year.

Another company that has adopted the quality path to progress and growth is Thermax Private Ltd, leading boiler manufacturers. According to chairman and managing director R.D. Aga, “Building quality requires a will and a commitment. And this has to start at the top.” He adds, “In the final analysis, quality is not just a product, or just a package of services, it is a way of life.” It is probably this outlook that has enabled the company to do well on the export front. Last year, the company’s exports touched Rs.17.2 crore on a turnover of Rs.108.3 crore, making it the fifth largest exporter of engineering goods in the country.

The message is getting through; companies are beginning to focus on customer satisfaction. Even public sector giant SAIL is reorienting its philosophy. Says chairman V. Krishnamurthy, “We should be in business to serve the consumer. And only when we are able to serve the Indian customer to his full satisfaction will we be able to serve the international customer.” This philosophy is being rapidly implemented at SAIL. Adds Krishnamurthy, “The process of change is taking place at SAIL. The first thing we brought about is consumer awareness or a market-oriented approach. Not only has interaction with the customer improved, but 85 per cent of what is produced in the steel plants goes directly to indentified customers (according to customer specifications). Four to five years ago, it was barely 40 per cent. But we have still not achieved our objectives of total customer satisfaction.”

Rigid tests

Bajaj Auto, the giant scooter manufacturer, has adopted the concept of total quality management with a sharp focus on maximum customer satisfaction. Says N.C. Agarwal, deputy general manager for quality assurance, “At every stage of the product manufacturing cycle, the components are put through a rigid quality test and only then is the batch passed.”

One of the ways the company keeps track of customer problems is through a dealers’ and service engineers’ conference held every alternate year. ‘We take these conferences very seriously and make sure that the problems of customers raised in these meetings are dealt with quickly,” says. P.V. Santurkar, general manager, works. And, the company is not resting on its laurels - it is constantly investing in training and equipment. For example, a BAIRD Spectrovac for metallurgical analysis was recently imported at a cost of Rs.17 lakh from the US.

The problem of quality is more acute in the small scale sector. This is largely the result of obsolete technology and lack of managerial effectiveness. As a result, government agencies are getting into the act. The Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI) , for example, has initiated a number of schemes to aid small scale industry (SSI) units in modernising and bringing about structural improvements for quality production. Says S.S. Nadkarni, chairman and managing director of IDBI, “The importance of the small scale sector cannot be overemphasised, as its contribution to industrial production is quite significant.”

In order to provide SSI units with funds for modernisation, IDBI is operating a refinance scheme, which essentially gives loans on concessional terms. According to G.P. Gupta, general manager of IDBI, the disbursement to date is around Rs.24.1O crore for 281 projects. He says, “Since modernisation is to improve quality, we reduce the interest rate by 0.5 per cent if the SSI unit has an ISI rating.”

Another serious problem that SSI units face is lack of access to many aspects of design and process control and developments in technology and managerial skills which are crucial to quality. To that end, the IDBI has set up a separate technology department to assist in creating a technology database, disseminating information on developments in technology and technology transfers. Says Gupta, “We are endeavouring to support green field projects like a CAD/CAM centre at Trivandrum, a prototype plant for generating electricity from tidal waves in Orissa, and a project for the development of enzymes at Bangalore, among many others.”

All said and done, the main reason for the backwardness of Indian industry in the crucial area of quality is lack of competition. Says Shah, “Competition is the key. But we have to be cautious and move slowly because we have had a sheltered economy up to now, and therefore change should be gradual. We should create the right conditions for internal competition first.”

Nadkarni of IDBI, however, maintains that there should be both internal and external competition simultaneously. To deal with cheaper, imported foreign products he suggests the imposition of tariffs and customs duty. This, he feels, will give Indian industry the necessary stimulus.

The general consensus among industrialists, whom Business India spoke to, was that competition (mostly internal) was healthy and that further liberalisation should give it the right impetus. Certainly the effect of liberalisation on Indian industry to date is quite visible. Says Nadkarni, “The impact of competition is quite apparent in the two-wheeler industry, light commercial vehicle sector, and in specialised spun yarn and cement.”

Collective action

But, as Lulla rightly points out, “If International competition in quality is to continue to grow at the pace prevailing in the eighties, the result will be that our deficiencies will become conspicuous. In that event, collective action across companies and industries will be required on a national basis.” He suggests the establishment of mandatory quality standards and national quality goals for exports. Also, he feels that national institutions are required to organise and conduct training programmes on quality management. “Business schools should include a special curriculum on quality management,” says Lulla.

The Confederation of Engineering Industries (CEI) has set up a total quality management division in Delhi. Through this, the CEI has managed to bring about a greater awareness of philosophy related to quality among its members. Says Janak Mehta, adviser to the division, “We are where the Japanese were in the fifties and the gap in development is about 50 to 60 years. We want to bridge that gap 10 to 15 years.”

But one must not forget that other NIC countries are also becoming more competitive. China, Thailand and Indonesia, among many others, are looking beyond their borders for markets to sell their goods and services in. If we have to be ahead of our competitors, we will need a political commitment towards quality and efficiency. This commitment will then have to translate into action by industry leaders.

CREDITS: Suresh Lulla, Founder & Mentor, Qimpro Consultants Pvt. Ltd.