In the days when “good enough” or “chalta hai” was good enough, a company expected that as much as seven per cent of the parts it received and seven per cent of the goods it shipped out would be defective; and that figure does not include the number of defective parts caught by inspectors and not shipped. Today, some of the best quality companies no longer count the number of defects per hundred but the number of defects per million.

Corning Glass Works supplied the first glass to Alan Dumont when he invented television in the 1930s. Corning used to consider itself outstanding at making TV tubes and the glass panels that go in front of them. A TV set manufacturer who bought glass from Corning could reject a panel if it had a bubble in it only 20 one-thousandths of an inch in diameter. Customers were rejecting only one in a hundred, or one per cent.

Then, in the 1970s, the Japanese came along and raced off with the TV market, including the market for TV glass. Four of Corning’s five glass plants in the United States closed. “We thought we were darned good”, recalled James Houghton, Chairman of Corning. “But our customers were talking in parts per million, and one per cent is 10,000 parts per million.” Houghton, the great great grandson of the man who founded the company in 1851, made quality improvement the focus of his tenure when he became Chairman in 1983. By 1987, Corning’s one remaining TV glass plant at State College, Pennsylvania had improved its performance ten-fold and was throwing out only 1,000 parts per million. Sony, with some condescension, now began buying glass from the plant, rejecting fewer than 100 out of a million pieces.

The lower-case letter “sigma” in the Greek alphabet (s) is a symbol used in statistical notation to represent the standard deviation of a population. Standard deviation, is an indicator of the amount of variation or inconsistency in any group of items or in any process. For example, when you buy an idly at an Udipi restaurant that is nice and hot one day, lukewarm the next - that is variation. Or if you buy three shirts of the same size and one is too large, that is also variation. In fact, there are infinite examples of variation because everything varies to some degree or another. Variation is a part of life. Another example: When your flight arrives at an airport, you never know if it will be five minutes or 20 before your luggage gets to baggage claim.

In 1987 Motorola set a goal to achieve Six Sigma quality by 1992. The objective in driving for Six Sigma performance was to reduce or narrow variation to such a degree that Six Sigmas - or six standard deviations of variation - could be squeezed within the limits defined by their customer’s specifications. For many products, services and processes that meant a hugh and tremendously valuable degree of improvement.

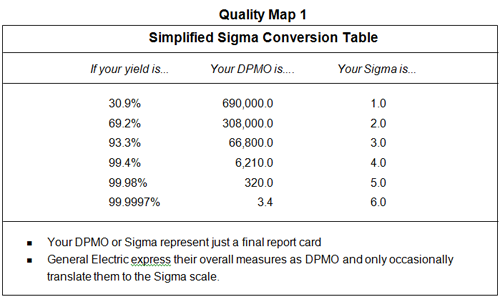

Sigma levels of performance are also often expressed in Defects per Million Opportunities or DPMO, as shown in Quality Map 6. DPMO simply indicates how many errors would show up if an activity were to be repeated a million times. By factoring in opportunities for defects in the calculation, Motorola made it possible to compare performance across different processes.

Some people draw the false conclusion that a “Six Sigma Organization” like General Electric or Motorola has actually reached this quality nirvana all across the board. This is far from the truth. They may have achieved this standard in some processes, but no company has more than a few processes at that level. On the other hand, just taking all your processes to Four Sigma (99.4 per cent yield) would be an enormous achievement for any Indian company I can think of.

Forbes Global is sought for its macro-economic reviews and corporate analysis. In a marked departure, this US based business magazine recently zeroed in on Bombay’s dabbawallah. The dabbawallahs are the lunch logisticians who deliver 150,000 lunch boxes to office goers from their homes everyday. Forbes analyzed them scientifically and rated them as if they formed a corporate body.

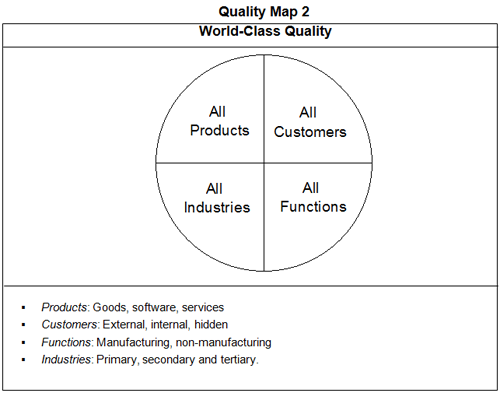

The dabbawallahs scored a Six Sigma performance rating, a benchmark reserved for Motorola and General Electric. The key lesson learned is that stretch quality improvement objectives are equally applicable to both the manufacturing and service sectors, technology-driven or otherwise. In fact, the definition of world-class quality encompasses all products, customers, functions and industries (refer Quality Map 7).

While “dollars” and statistical tools tend to get the most publicity, the emphasis on customers is probably the most remarkable element of Six Sigma at General Electric. As Jack Welsh, CEO, explains it:

“The best Six Sigma projects begin not inside the business but outside it, focused on answering the question - how can we make the customer more competitive? What is critical to the customer’s success?... One thing we have discovered with certainty is that anything we do that makes the customer more successful inevitably results in a financial return for us”.

An extract from World-Class Quality: An Executive Handbook, Suresh Lulla. Reproduced with permission, © 2003, Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Co.Ltd.,West Patel Nagar, New Delhi, 2003.

CREDITS: Suresh Lulla, Founder & Mentor, Qimpro Consultants Pvt. Ltd.