In part one; we described the applications of surveys in the business environment. We also discussed the types of satisfaction surveys and basic survey methods. In this part, we start-off with a short discussion on the trade-off between conducting the survey in-house and seeking the assistance of an external consultant. We then provide some words of caution on the choice of survey for measurement; and then finally proceed to introduce some basic definitions and terminologies which will pave the way for the following article.

In-House or Consultant

The main advantage of executing a survey by own staff is saving money and developing internal capabilities. However, it’s highly advisable to seek the assistance of a professional source; especially if conducting surveys is not a common activity in the organization and/or if the questionnaire instrument needs to be designed from scratch. Advantages for seeking the assistance of an external consultant include:

- More professional. Undoubtedly, conducting surveys successfully requires specific set of competencies that are not commonly available in-house; and typically are not present in a single individual.

- More accountability. Since it is a paid-for project, the organization may hold the consultant accountable for achieving the survey objectives within the defined project parameters.

- More timely. In-house team members are usually busy with other work duties. Hence, an external consultant is more likely to complete the study on time.

- More independent. Sometimes companies prefer a third party to carry out the survey to ensure transparency and objective results.

- More anonymous. In some surveys, where employees are asked to cast their opinion on the company or its management, resorting to an outsider to administer the survey motivate respondents to be more honest and forthcoming.

Between seeking external help and doing it internally, there are other in-between options available to the organization:

- Outsource the design.

- Outsource the analysis.

- Outsource the Subject Expert.

- Outsource the Project Leader.

Since design and analysis are interrelated, they are better tasked together. It’s advisable that the whole job either be done internally or given to an external consultant. In some cases, however, the nature of the survey requires that the services of external subject matter experts be sought.

Surveys: Words of Caution!

Surveys are not the only modes for measuring satisfaction or inviting input or feedback on a certain subject; there are surely alternative, and sometimes more appropriate, methods including focus groups, workshops, symposiums, expert opinions, and benchmarking. To evaluate a new dish on the menu, a restaurant might want to solicit the opinion of a group of selected patrons or even a single reputable taster. To evaluate the quality of its operations, a local oil company might find benchmarking with a reputable international oil company more appropriate than surveying customers.

Limitations of surveys include:

- Survey success depends on subject’s willingness to share his/her true thoughts; as well as his/her honesty, memory, and ability to respond (express him/herself in interviews).

- Surveys are not suitable for studying complex issues; focus groups and experts are often more suitable.

- Responses are sometimes based on perception, which may not reflect reality; e.g. the perceived quality is different from objective quality.

- Responses may be biased by experience of other organizations, which may not be similar to the studied organization.

- Surveys take time to execute; by the time they are finished, decision is already made! Or the context may have already changed.

- In many surveys the sampling is not random (random sampling may be difficult or costly); this makes inference on the population incorrect.

Criteria for the selection of appropriate measurement tool include effectiveness, quality, practicality, timeliness and economy.

- An effective tool is one that best achieve the purpose;

- A quality tool is one that provides for accurate responses;

- A practical tool is one that is easy to execute;

- A timely tool is one that can yield the required results when needed; and

- An economic tool is one that meets the budget constraint.

Of these criteria, ‘effectiveness’ is undoubtedly most important. A lot of money, effort, and disappointment can certainly be averted if the company first specifically and clearly states the purpose(s) of the survey; and then indisputably decides that such purpose(s) cannot be addressed with alternative more suitable measurement tools. Nothing more erroneous than a novice analyst prematurely promoting a survey study to her manager; and to make matter worse, pushing for a certain data collection instrument (i.e. questionnaire) without any objective justification for her selection! Such actions should quickly be viewed as early warnings of failure.

Basic Survey Terminologies

The population (those eligible to be surveyed) could be customers, users, managers, employees, or suppliers. Often times it is not possible to survey the whole population, so a representative sample (i.e. subset) of the population is randomly selected. The property of randomness is critical to ensure result validity. It’s erroneous to assess a trainer’s competency in quality based on the evaluation of only one workshop on quality management; a more valid evaluation would include evaluations from workshops covering other quality topics. Technically speaking, a sample is said to be random when each member in the population has an equal chance of being selected. Needless to say that it’s not always easy to meet the randomness requirement; this is due to the difficulty of accessing certain members in the population. However, every effort should be made to get as close as possible to ‘pure’ randomness.

Randomness violations (i.e. non-random sampling) may take different forms as follows:

- Accessibility/ availability sampling; where members of the sample are chosen based on their relative ease of access; e.g. sample friends, co-workers, or shoppers at a single mall.

- Link sampling; where a sampled participant refers a friend; who in turn, refers a friend, etc.

- Selective/ judgmental sampling; where members of the sample are selected based on personal judgment and/or biases.

- One group sampling; where members of the sample belong to a certain stratum of the population who happen to have similar opinions/biases.

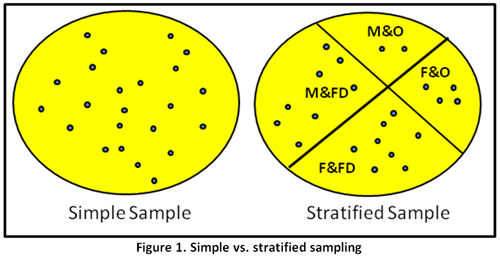

In business surveys, randomness is often administered in conjunction with stratification (i.e. dividing the population into groups of homogeneous members); e.g. male/female, Kuwaiti/GCC/Arab/Non-Arab, 18-25/26-40/over 40 age groups, and MAA/MAB/SHU refineries at Kuwait National Petroleum Company (KNPC). Stratification ensures representation of all groups in the sample; it also allows for inter and intra stratum analyses and recommendations. For example, through female/male stratification, we may learn the opinion of female college students of an entertainment program; we may also compare that opinion with the opinion of male. Stratification often results into larger sample size (thus more effort and cost). Therefore, it should not be used, unless the analyst suspects that it matters. For example, male/female stratification may not be warranted if the objective is to solicit students’ opinion of a new curriculum; whereas, it probably matters if the objective is to solicit their opinion on future work preferences. One or more stratification may be warranted for some applications; for example, KNPC may decide to apply two stratifications: male/female and office/field (Figure 1). It can even go further if the objective calls for it by stratifying the field into the three refineries MAA/MAB/SHU.

Sample Size

A key decision in surveys is the determination of sample size; i.e. how many members to select from the population? It is important to note that the results of the analysis will be used to make decisions (i.e. inference) on the whole population and not just the sample. Therefore, the size of the sample affects the goodness of decisions. In a forthcoming article we’ll discuss the quality of inference on a statistical basis; however, we’ll do the same here but using intuitive bases.

- The sample size is directly related to the population size. This makes sense; a larger sample size needs to be taken if the population size is large.

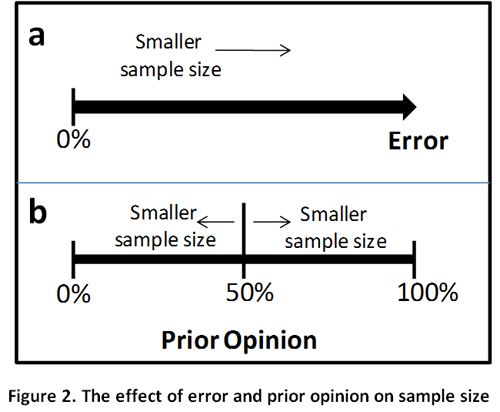

- The accuracy (or error) of decision is directly related to the sample size. This makes sense; as error of inference will tend to zero as the sample size approaches the population size (see Figure 2a).

- The prior knowledge of opinion tendency affects the sample size. i.e., complete ignorance on whether the opinion on a certain issue is one way or another (i.e. 50%) will lead to the largest possible sample size (see Figure 2b). This makes sense; why one would need to take a large sample (or conduct the study at all) if previous study showed that over 90% of population favors a certain issue. In other words; a change from ‘favoring’ is very unlikely. However, if the previous study showed a 55%, the result of the new study could go either way; thus a large sample size needs to be taken to ensure the validity of the results.

There are two ways to determine the sample size:

- Test sampling; where the sample size is determined based on the result of an initial small sample.

- Dynamic sampling; where sample size is first determined based on complete ignorance (50%); then it’s continuously revised as results are obtained. This was the approach undertaken by the author on a survey study for KNPC where it’s expensive to do test sampling1. The study calls for soliciting the opinion of high rank company managers via a questionnaire administered in a workshop setting. At the conclusion of the first workshop, it was clear that the opinion is sharply pointing to one direction (close to 90%); this was further reinforced in the second workshop. The analysts decided not to administer more workshops (save efforts and money) as the results provide the required inference given the pre-set error and confidence levels.

Sources

- “Measurement of opinion of beneficiaries on the Mechanism for Supporting National Industry in the Local Oil Sector.” Final Report, Kuwait National Petroleum Company, study conducted by Gulf Lead Consultants, 2006.

Tariq A. Aldowaisan has a Ph.D. from Arizona State University in 1990. He is currently an associate professor of industrial and management systems engineering at Kuwait University, and a general manager of Gulf Lead Consultants. He has professional certifications from reputable organizations; they are Certified Safety Professional (CSP) from the Board of Certified Safety Professionals (BCSP), USA; and Certified Quality Engineer (CQE), Certified Quality Auditor (CQA), and Certified Quality Manager/ Organizational Excellence (CQM/OE) from the American Society for Quality (ASQ). He has over 20 years consulting and training experience in quality, organizational excellence, management systems design, and occupational safety.

CREDITS: Dr. Tariq A. Aldowaisan