This article reports on the experience of Kuwait National Petroleum Company (KNPC), the only refinery company in Kuwait, in utilizing the audit as a tool to improve its relationship with its local suppliers (contractors, manufacturers, and consultants.) The audit in traditional management systems relies on a relatively invariant checklist of items (audit protocol). The checklist is developed based on some standard; e.g. ISO 9001 or 14001 management system standards, that is customized to account for context particulars such as type of operations, number of sites, etc. The output of the audit process is an audit report that details incidents of non-compliances. These incidents reference the violated clauses/requirements; which generally remain unchanged from audit to audit.

The adopted approach by KNPC is rather unique in that audit requirements, stipulated by parent company Kuwait Petroleum Corporation (KPC), are considered for change from audit to audit; i.e. dynamic. The proposed dynamic audit could potentially help to overcome many of the shortcomings experienced in the current practice of ISO 9001 and other management system standards.

Traditional Audit

Audit is a quality management tool used to verify continual compliance with a preset standards or requirements. According to ISO 19011, Audit is a “systematic, independent and documented process for obtaining audit evidence and evaluating it objectively to determine the extent to which the audit criteria are fulfilled.” The audit criteria (or audit protocol) are “set of policies, procedures or requirements” against which audit evidences are compared. Audit evidences are generally obtained through interviews, observations, and/or records and documents. In general, the strongest evidence is the records/documents because it is hard to dispute.

Factors contributing to a successful audit are:

- Effective and efficient audit program that specifies all the activities necessary for planning, organizing, and conducting the audits. An effective audit achieves its purpose; uncovering serious or potentially serious non-compliance incidents. Whereas, an efficient audit gets the job done economically and with minimal disturbances to the auditee.

- Auditor competency; which is a function of relevant education, credible audit training, ‘right’ auditor personal qualities and interpersonal skills, and auditor’s context knowledge and experience.

- Cooperative and committed auditee; who demonstrate openness and support throughout the audit process from planning to reporting; as well as commitment to act on non-compliances and recommendations.

At the conclusion of the audit, an audit report is issued. The report consists of non-compliance incidents and improvement recommendations. Reported non-compliance incidents must reference the violated clause in the audit protocol. Improvement recommendations or observations are usually precautionary notes to avoid potential non-compliances. Once the company is found compliant to a clause through certain provisions, it remains compliant in future audits as long as the provisions stay intact.

The KPC Mechanism

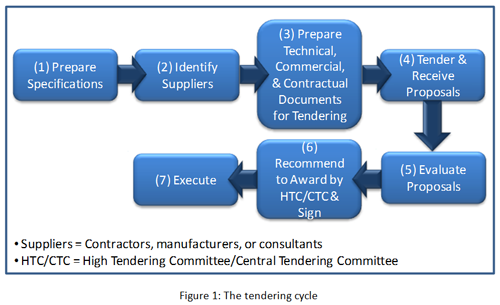

Twenty five relatively broad requirements on local supplier support are mandated by the KPC Mechanism. The requirements are grouped according to the tendering cycle depicted in Figure (1); and augmented with a number of additional general requirements. Step 6 of the tendering cycle is only necessary if the contract size (greater than $3.3 Million) requires recommendation by the High Tendering Committee (HTC), a KPC level committee, and/or Central Tendering Committee (CTC), a government level committee.

Some KPC requirements have various facets of interpretations and alternative modes of implementation; all of which are acceptable though at differing degree of effectiveness.

KNPC Dynamic Audit

The following steps describe the dynamic audit approach adopted by KNPC in assessing compliance with KPC requirements:

- Develop audit protocol by determining approved implementation modes (AIMs) for all clauses. This is done as follows:

- Directly infer implementation modes for a specific requirement.

- Use already approved implementation modes from previous audits for addressing broad requirements.

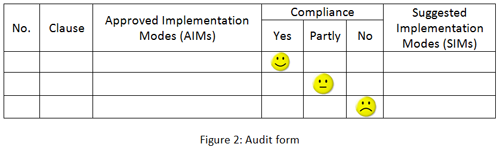

- Secure approval from KNPC steering committee for implementation modes suggested from the last audit (Figure 2).

- Use a three-option compliance outcome as follows (Figure 2):

- Yes; when achieving compliance with all AIMs for a given clause, or when the cause for non-compliance is due to external (i.e. beyond KNPC control) causes.

- Partly; when achieving compliance to some AIMs for a given clause, or when compliance is judged to be inadequate.

- No; when failing to achieve compliance to all AIMs.

- Suggest (new) implementation modes (SIMs) for future audits. The sources of such suggestions are the auditor and audited organization personnel; and they are often generated as a result of the field audit experience.

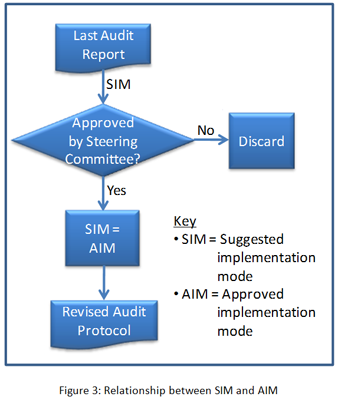

Figure 3 shows that the dynamic nature of the audit is due to the revision of the audit protocol at the conclusion of each audit event. Unlike traditional audit, compliance in dynamic audit may change from complete compliance to partial or no compliance if a SIM in the previous audit report becomes or supersedes an existing one or more AIMs on the next audit protocol; and organization is found to be non-compliant to the newly introduced AIMs on the next audit event. This supports the concept of business excellence; where unlike standards of management systems, the requirements keep changing (i.e. dynamic).

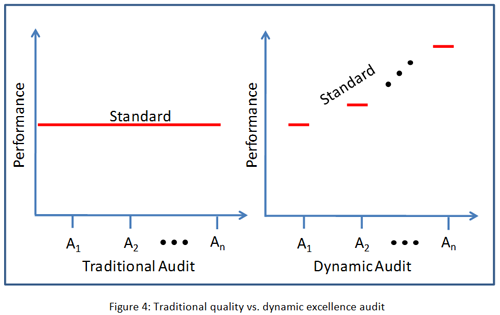

Figure 4 conceptually compares between traditional quality audits and dynamic excellence audits. In the latter, performance is compared against a new more effective and challenging standard in each audit event.

Figure 4 conceptually compares between traditional quality audits and dynamic excellence audits. In the latter, performance is compared against a new more effective and challenging standard in each audit event.

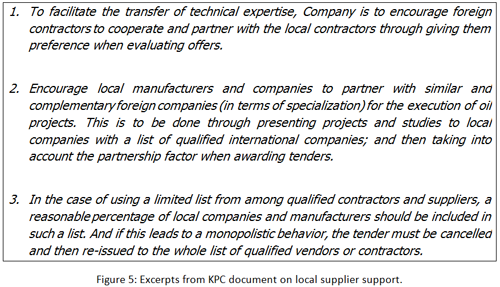

To demonstrate the working of the dynamic audit, we consider three clauses from the KPC document on local supplier support (Figure 5.) The first clause requires Company (KNPC) to “encourage foreign contractors to cooperate and partner with local contractors.” It goes on to suggest a mode of encouragement “giving foreign contractors preference when evaluating offers.” When auditing on this clause, one simply checks if a formal system to give such preferential treatment does exist. If it does, a “yes” is entered for compliance in Figure 2. If system is found to be ineffective or a more effective system can be proposed either by the auditor or interviewed individuals during the audit, then such proposal is entered in the SIM column. At the conclusion of the audit, the report is presented to a steering committee composed of relevant managers. If they approve the SIM, it becomes AIM in place of the old AIM. In the following audit, if the organization continues to work with the old preferential treatment system, a “no” for noncompliance is entered in Figure 2.

To demonstrate the working of the dynamic audit, we consider three clauses from the KPC document on local supplier support (Figure 5.) The first clause requires Company (KNPC) to “encourage foreign contractors to cooperate and partner with local contractors.” It goes on to suggest a mode of encouragement “giving foreign contractors preference when evaluating offers.” When auditing on this clause, one simply checks if a formal system to give such preferential treatment does exist. If it does, a “yes” is entered for compliance in Figure 2. If system is found to be ineffective or a more effective system can be proposed either by the auditor or interviewed individuals during the audit, then such proposal is entered in the SIM column. At the conclusion of the audit, the report is presented to a steering committee composed of relevant managers. If they approve the SIM, it becomes AIM in place of the old AIM. In the following audit, if the organization continues to work with the old preferential treatment system, a “no” for noncompliance is entered in Figure 2.

Clause 2 in Figure 5 specifically calls on local contractors to partner with international ones, with a requirement of KNPC to facilitate that partnership through providing a list of probable prequalified international organizations whenever a request for tender is made. Additionally, the clause states that KNPC would take into account the partnership factor when making the award. When auditing for this clause, the auditor checks first if KNPC does provide such a list when requesting for tender (1st AIM), and then check if KNPC does take that into account when making the award (2nd AIM). When audited on this item, it was found that KNPC does comply with the first AIM; however, it does not comply with the 2nd AIM. So a partial compliance is recorded on Clause 2. The auditor noted that KNPC did not comply with the 2nd AIM because it is difficult to comply with this factor; and people cannot think of a way to do it. The auditor recommended in the SIM that KNPC contact parent company for opinion. In the following audit, the situation didn’t change, however, KNPC has contacted KPC, but it did not receive a response. So, the auditor checked “yes” for total compliance as the cause of non-compliance with the 2nd AIM is beyond KNPC control.

Clause 3 aims to encourage participation of local suppliers through assuring that they constitute a ‘reasonable’ percentage of qualified companies on a given tender. One of KNPC AIMs with respect to this clause requires that KNPC does not seek a non-local company should six or more local companies bid; otherwise, the tender shall be open to all local and non-local companies. The auditor finds opening the tender to all companies if less than six local companies bid contradicting with the ‘reasonable’ percentage notion. Hence, a SIM recommends maintaining a certain minimum percentage of local companies by controlling the number of non-local companies. So, the auditor checked “yes” for compliance; however, should the steering committee approves the SIM, the decision might be different in the next audit.

In summary, the dynamic audit forces continual improvement through continuous alteration of the requirements. It also penalizes status-quo; an organization compliant to a given requirement with certain provisions could potentially become non-compliant although the old provisions are still in place. In addition, dynamic audit has the advantage of encouraging the auditor and auditee to suggest better compliance provisions, and also engages decision makers (steering committee) to make a decision on converting a suggested implementation mode into an approved implementation mode.

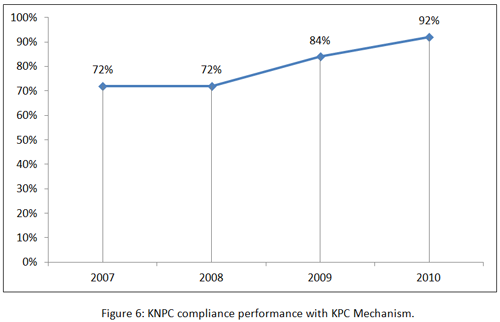

KNPC continues to implement dynamic audit. Figure (6) shows its compliance performance since 2007. KNPC has contracted the same consulting company, Gulf Lead Consultants (GLC), who has worked with KNPC on its Supplier Partnership Program since its inception, to conduct audits on Kuwait Oil Company (KOC), Petrochemical Industry Company (PIC), and Kuwait Oil Tanker Company (KOTC). The findings of these audits along with the experience KNPC has gained from implementing its dynamic audit program shall be used to suggest changes on the KPC Mechanism itself.

Examples of improvements brought about by dynamic audit are:

- Generalizing the specification in the material catalogue to the largest extent possible by requiring the documentation of the exceptional cases under which specification is not generalized. This gives KNPC widest possible access to available products; and provides opportunity for qualifying new products.

- Requiring a minimum number of 10% local companies in the list of invited companies even if the number of local companies is less than 6. This enhances the opportunity of local companies.

- Modifying the current performance quality index (PQI) used to evaluate contractor performance by adding a dimension related to contribution of local products and activities.

A more strategic impact of dynamic audit is the realization that there is a need for the establishment of an organizational unit – Supplier Services Center – at KNPC, which is dedicated to address local suppliers’ needs. The Center provides 16 services; several of which are triggered by the dynamic audit; e.g. supplier partnership advisory council (SPAC) which has membership from both sides and meets regularly to work for the improvement of relationship between the two sides.

Dynamic Audit to Overcome ISO 9001 Shortcomings

Despite its worldwide popularity, ISO 9001 did not succeed in many instances in promoting continual improvement, or even yielding consistent quality. Several articles reported serious problems with the application of ISO 9001; e.g., Paul Scicchitano “Is an Elephant Hiding behind ISO 9001 Numbers?” in Quality Digest, Feb. 2010; Girdhar J. Gyani “Crisis of Credibility” in Quality Digest, August 2007; and Tariq Aldowaisan & Ashraf Yousef “An ISO 9001:2000-based framework for realizing quality in small businesses” in OMEGA The International Journal of Management Science, vol. 34, 2006; Ashok Thakkar “The Rise and Fall of ISO 9001” in Quality Digest, Sept. 2003.

The main reported problems can be summarized in the following points:

- A quality management system (QMS) that does not add value; and is merely there for certification and image. This is often due to overreliance on external consultants in the development of QMS. Many of these consultants, under time and budget pressures, end up delivering a ready-made documented system and generic templates that do not ‘fit’ the organization’s business.

- Lack of appreciation and knowledge of ISO 9001 and certification process by executives and top management; which is largely due to their lack of involvement in the development and operation of QMS.

- A QMS that restricts innovation and constrain operation. This is due to over documenting internal processes. Although ISO 9001 tried to mitigate this problem by requiring documentation of only six system processes, many organizations continue to over document. It seems that the reason for that is organization’s lack of internal capabilities to develop new documentation when needed; so they try to ‘play it safe’ and ask external consultants to document ‘everything’.

- Inconsistent auditing procedures by registrar auditors leading to loss of credibility. This is attributed to lack of oversight by certification body.

To overcome the above shortcomings, ISO 9001 has to have a provision whereby requirements are subjected to change; and thus established compliance to a certain requirement through some practice at a given audit event may become non-compliance in subsequent audit events if requirements are not changed; similar to the adopted dynamic audit approach by KNPC. This forces organizations not to over rely on external consultants to develop their systems. Moreover, the dynamic audit will encourage learning and innovation as well as it will pressure continual improvement in the organization. And by suggesting new implementation modes (SIMs), commitment of the executives and top management will be enhanced as they will be part of the auditing cycle to approve these suggestions.

Dr Tariq A. Aldowaisan is an associate professor of industrial and management systems engineering at Kuwait University and a general manager of Gulf Lead Consultants, Kuwait. He received all his degrees in industrial and management systems engineering from Arizona State University (Ph.D. in 1990); and since then he worked at Kuwait University. He is a Certified Safety Professional (CSP) from the Board of Certified Safety Professionals (BCSP); and Certified Quality Engineer (CQE), Certified Quality Auditor (CQA), and Certified Quality Manager/ Organizational Excellence (CQM/OE) from the American Society for Quality (ASQ). He has over 20 years academic, consulting and training experience in quality, organizational excellence, strategic planning, management systems design, and occupational health and safety. Elaf A. Ashkanani is an assistant consultant at Gulf Lead Consultants, Kuwait. She received her bachelor degree in industrial and management systems engineering from Kuwait University and after graduation worked at Gulf Lead Consultants for four years. She has performed several consulting work in ISO 9001 and management system development.

CREDITS: Dr Tariq A. Aldowaisan & Elaf Ashkanani