Car makers and television manufacturers, banks and hospitals, airlines and couriers, electricity boards and municipalities - all afflict us with poor quality. We add to this misery through our own frequent failures to do things right the first time in our personal lives. The burden that poor quality imposes on society is incalculable. When companies are asked what poor quality costs them, their guess is at around three to five per cent of sales. But when they actually calculate their costs they find it more like 20 to 30 per cent.

In the late 1980’s,Tata Steel, Jamshedpur, resolved to make better products. This was before the liberalization of the Indian economy. The chairman, Russi Mody and the managing director, Dr J J Irani set out on a global search for quality knowhow. On the top of their shortlist was The Juran Institute, Connecticut, and through them, their Indian affiliate, Qimpro Consultants. Dr Juran’s experience with Bethlehem Steel was considered to be particularly relevant. As a result, Mody and Dr Irani invited Qimpro to address their top management team at Dimna, an executive training centre of the company, about 50 kilometers from Jamshedpur. The unique feature of this centre was “style”, that excluded telephones or any other convenient means of communication. In other words, Qimpro had a captive top management audience.

In those days, Tata Steel, a blue chip company, could sell any grade of steel it produced. The marketing function had been reduced to one of rationing1. Consequently, quality was not considered to be a major issue. The two key leaders anticipated a change in the business environment and proactively set a strategic goal to make superior quality products through their 65,000 employees. The prevailing rejection rate was three per cent in those days.

The first step in Juran’s approach for quality improvement is the estimation of the costs of poor quality. Due to the non-availability or accessibility of hard data at Dimna, the top management team depended heavily on the best estimates provided by their finance director, Ishaat Hussain. The first estimate of the costs of poor quality was a simple three per cent of sales. By the end of the first day, the second estimate of the same costs grew to nine per cent of sales. On commencement of the second day of interaction, Hussain whispered in Mody’s ear ‘over 25 per cent’. A deafening alarm went off. This resulted in an instant buy-in from the entire top management team. The quality opportunity was accepted as being supremely attractive. Russi Mody articulated a strategic quality goal: Halve the costs of poor quality in five years.

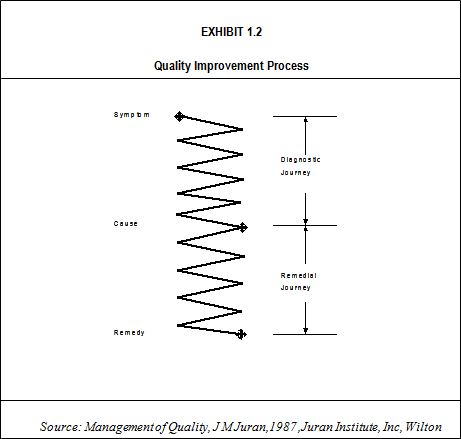

While there was an initial enthusiastic buy-in, the power of Dr Juran’s quality improvement methodology (Exhibit 1.2) was appreciated fully only after Tata Steel achieved dramatic results through the first few Bellwether projects.

Diagnostic Journey

- Pareto analysis of symptoms

- Theorize on causes of symptoms

- Test theories

- Narrow list of theories

- Conduct experiments to establish proof of cause.

Remedial Journey

- Consider and propose remedies

- Test remedy

- Action to institute remedy

- Control at new level.

For example, the bogie bottom pouring project at the LD shop registered savings of the order of Rs 2.3 crores per annum (on a recurring basis) according to A D Baijal, senior divisional manager (planning). In addition, the tubes variability project at the Tubes Division, recorded savings of Rs 1.7 crores per annum (on a recurring basis) according to the division’s head, F A Vandrevala. It should be noted that Dr Irani personally reviewed the progress of these project teams.

Following the success of the first five pilot projects, Tata Steel established an apex council and several divisional quality councils. The apex council provided strategic direction, whereas each divisional quality council focused on executing quality improvement projects and building the necessary infrastructure for project identification. Along the way, Tata Steel sought ISO 9000 certification, and also conducted a self-assessment exercise against the Malcolm Baldrige criteria. The latter was facilitated by Frank Tedesco from The Juran Institute. The apex council assessed Tata Steel at a level under 200 on a maximum of 1000 in 1991. The question arose, “Is this blue chip company capable of world-class quality?” The rest is now history.

In the year 2000, Tata Steel won the first JRD Quality Values Award achieving a score in excess of 600 on a maximum of 1000. The JRD QV evaluation covers corporate areas such as leadership, strategic planning, customer focus, process management, human resource focus, information and analysis, and business results. The award competition is internal to the Tata Group of Companies and is the highest internal recognition for total quality. The JRD QV Award criteria are in line with those of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award in the US.

It took Tata Steel ten years of determination to achieve excellence in manufacturing. Today, it is the world’s second lowest cost producer of hot rolled coils. Over this period, Tata Steel has shed 30,000 jobs without any industrial unrest. In July 2001, the company was ranked first among 12 of the world’s top steel firms by the US consultancy organization, World Steel Dynamics.

According to Dr Juran, costs of poor quality can generally be classified into four broad categories.

- Internal failure costs: Scrap, rework, failure analysis, re-inspection, retesting, avoidable process losses, downgrading

- External failure costs: Warranty charges, complaint adjustment, returned material, concessions

- Appraisal costs: Incoming inspection and testing, in-process inspection and testing, final inspection and testing, product quality audits, maintaining accuracy of testing equipment, evaluation of stocks

- Prevention costs: Quality planning, new-product review, process control, quality audits, supplier quality evaluation, training. Prevention costs are incurred to keep failure and appraisal costs at a minimum.

- Costs of poor quality (COPQ) consist of:

- failure costs

- appraisal costs

- prevention costs

- COPQ = 20 per cent of sales (conservative estimate)

- Profit = 10 per cent of sales (optimistic estimate)

- Strategic Goal: Double profit by halving COPQ, with no capital investment.

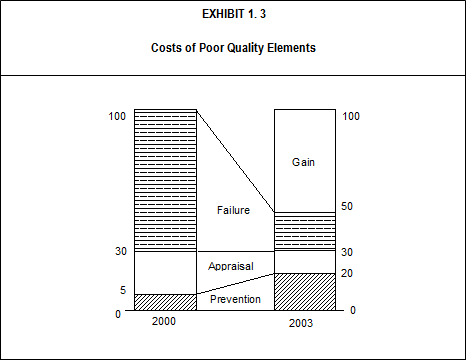

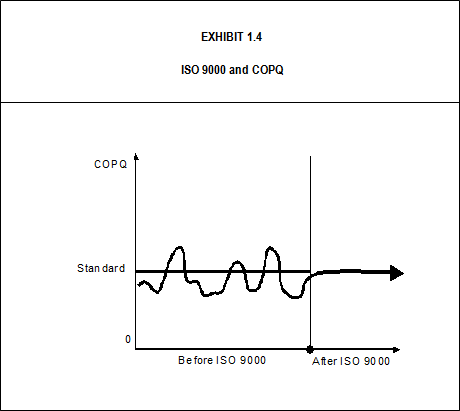

The ratios presented in Exhibit 1.3 will vary from company to company, industry to industry and from time to time. The means for achieving gains involve effective application of the quality improvement process. On the other hand, these ratios will not be greatly influenced by the implementation of ISO 9000 quality management systems, although the application of these standards may well reduce the incidence of disasters such as the one in Bhopal. It should be noted that the main objective of ISO 9000 is not to reduce quality related costs. It has no mechanism to do this. All it does is to smooth out variations as indicated in Exhibit 1.4.

The main objective of ISO 9000 is to contain variation. ISO 9000 systems maintain the standard.

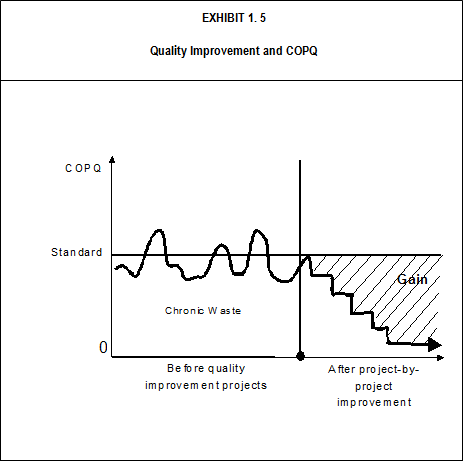

Focusing on appropriate prevention activities such as project by project improvement will reduce costs, and through the remedies applied will at the same time improve the quality systems in the places where they have the greatest impact on quality. Exhibit 1.5 highlights the basic difference between the two approaches. ISO 9000 quality management systems help to maintain the standard; the quality improvement approach helps achieve gains through challenging the standard.

Quality improvement projects address chronic problems. They challenge the standard. The gains achieved through a project-by-project approach go straight to the bottom line.

Many companies attempt to implement ISO 9000 before starting a world-class quality programme either because a demanding customer expects it or because a key competitor has done so and is attempting to capitalize on it. In such cases, there is a very high risk of these companies introducing the standard, not because they believe in the concept, but because they are forced to do so. This is the worst reason for doing anything. The company, in this case, will almost certainly end up with two systems, the one it shows the auditor, and the one it actually uses. Cynicism will be rampant, and senior management may be justifiably accused of not being quality conscious. Of course, costs of poor quality will multiply as a result of maintaining two systems.

These problems can be overcome if ISO 9000 is introduced as part of a world-class quality programme. With this objective, ISO 9000 may or may not be the first item on the agenda as in the case of Punjab Tractors, Mahindra and Mahindra (Tractor Division), Rane Engine Valves and many more. Each of these companies initially focused on making a habit of quality improvement, company-wide, and simultaneously harvesting the benefits of reducing the costs of poor quality. The primary objective of world-class quality management is to make organizations more competitive in order to dominate the field.

Items that would be subject to audit according to ISO 9000 may not even exist in a true world-class quality organization. For example, there is the case of the ISO 9000 auditor who went to a Japanese supplier in order to make an audit. After the audit, the company asked whether he had seen everything he wanted to see.

“Well almost”, he said, “I haven’t been able to find your goods inwards stores and finished goods stores”

“We do not have any,” he was told

“I would also like to see the stores for reject or substandard parts”

“We don’t have these either”, was the reply!

Dr Juran is at least partially responsible for the very wide circulation of the Motorola-Matsushita/Quasar story in manufacturing circles. He explains the concepts behind costs of poor quality with this example, in his foundation lectures on ‘Management of Quality’: In the mid 1970s, the Japanese electronics giant bought out a colour TV plant that had formerly been run by Motorola. Before it came under Japanese management, the Motorola factory had been running at a rate of 150 to 180 defects per 100 sets. Three years later, the defect rate had dropped to three or four per 100 sets! As a result, the costs of poor quality dropped from $22 million to less than $4 million, the number of in-plant repair and service employees was reduced from 120 to 15, and personnel turnover dropped from 30 per cent to one per cent per annum.

All this was possible through effort and marginal investment, including modified product designs that were less prone to field failure, changes in the manufacturing processes that reduced the risk of defect generation, and more reliable defect-free parts. In short, Matsushita utilized many of the basic quality management principles that the leading American experts had been preaching for 20 years. They did not use a revolutionary new technology, or a new work force. The key to their expertise in the field was intensive quality oriented management that brought with it targeted increases in quality and simultaneous and concomitant decreases in cost.

How the Japanese have achieved mastery of quality is not a mystery or miracle. The “secret” is no secret at all, and its key is not superior technology or robots, nor is it government assistance or macroeconomic forces. It is a management system - the quality control system taught by Prof W Edwards Deming and subsequently enlarged for leadership and quality improvement by Dr Joseph M Juran.

The NUMMI (New United Motors Manufacturing Incorporated) quality story is also vitally important to manufacturers across the globe. NUMMI is a joint venture of General Motors and Toyota Motor Company. In this venture, Toyota makes a version of the Toyota Corolla, and GM sells it under the Chevrolet Nova label. Toyota does the manufacturing in a GM plant at Fremont, California, which had been closed by GM due to low quality and low productivity. By all accounts, under the GM management, the Fremont plant was an industrial nightmare, with poor quality performance, low productivity, wildcat strikes, and incredible absenteeism.

Then, Toyota took over the operations and now NUMMI has the highest quality and productivity of the entire GM system. How was this accomplished? It was largely through implementing ideas similar to those used at the Quasar plant, and also through a series of quality management techniques that rely heavily on innovative employee relations and workplace reorganization. These interventions made it possible for NUMMI to utilize the skills and talents of the workers in ways that simultaneously enhanced quality, productivity, and employee satisfaction. Yet, NUMMI is not a particularly high-tech operation. In fact, actual manufacturing technology used in the plant is not as advanced as that utilized currently at some other GM plants. Moreover, the workers are some 2,500 of the 6,000 UAW workers who were laid off when GM closed the plant.

There are similar stories of manufacturing successes achieved by other leading Japanese companies, including Sony and Honda. The lessons learnt are also pretty much the same.

World-class quality begins and ends with the profit and loss account and the balance sheet. The current world-class management models, such as the Malcolm Baldrige Award, the European Quality Award and the IMC Ramkrishna Bajaj National Quality Award, reinforce the same conclusion. In the context of these models, the cost relationships that have the greatest impact are:

- Quality costs as a percentage of sales

- Quality costs as compared to profit

- Quality costs as a percentage of total manufacturing costs

- Effect of quality costs on the break-even point.

CREDITS: Suresh Lulla, Founder & Mentor, Qimpro Consultants Pvt. Ltd.